[ad_1]

Ever since Marlon Brando walked into that bar in 1953’s The Wild One in his Levi’s 501’s, Schott Perfecto biker jacket and engineer boots, the leather jacket has symbolised rebellion. The impact László Benedek’s film had on youth culture, filmmaking and movie stardom was immeasurable – though its most enduring legacy is not in Brando’s swagger, but the black leather jacket his hard-knuckled rebel dons.

At the time, The Wild One was considered such a threat to society that the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) refused to give it a classification for 14 years, citing its depiction of “unrestricted hooliganism”. The leather jacket itself was banned in American schools, considered a sign of criminal intent in and of itself. Since then, it has become a sartorial go-to for bad seeds, rebels and punks. Jeff Nichols’s latest film, the Tom Hardy drama The Bikeriders, which is in UK cinemas now, harkens back to this moment in American history – a time in which the leather jacket was a symbol of unrest and revolution, but also of belonging.

Before it became a cultural icon, the leather jacket was a utilitarian item of clothing, mostly worn by pilots and highway patrol cops to keep safe in the rain and harsh weather. Irving Schott, who’d started off making raincoats in a New York City basement that he sold door-to-door with his brother, designed the now-iconic Perfecto jacket in 1928, naming it after his favourite cigar. It was sold originally through Harley Davidson shops, meaning it intertwined from the start with biker culture. Later on, Schott was commissioned to produce the uniform for US Air Force pilots, creating the bomber jacket.

“It was always associated with dangerous sports,” Roger K Burton, stylist, costume designer, founder of the Contemporary Wardrobe Collection and author of Rebel Threads tells me. Dangerous sports and, ironically, authority.

“Leather was tough, it was warm for pilots at cold high altitudes and armies on the move; it didn’t tear easily,” points out film critic Christina Newland. “That’s the same reason bikers – who were often veterans – would have adopted it.” After World War II, the huge surplus of aviation leather jackets were supplied to the thrift system, making the item financially accessible. Riding their Harley Davidson choppers, “even the Hell’s Angels were aping the highway patrolmen,” laughs Burton. This symbol of stately order, practicality and uniformity would soon be repurposed as an emblem of anti-authoritarianism.

It was the movies that transformed biker and bomber jackets from a stately uniform into a symbol of counterculture and coolness. In The Bikeriders, married-with-kids truck driver Johnny (Hardy) is so inspired by Brando’s attitude in the film that he sets up his own motorcycle club, The Vandals. They are bonded together by their love of choppers, beer and an aggressive sense of community, symbolised by the leather jacket, their “collars”. In the opening scene, The Vandals’ Benny (Austin Butler) is assaulted in a bar because he refuses to take it off. “You’d have to kill me to take this jacket off,” he growls. Their leather jacket (sometimes a denim one too), is the uniform of the rebel.

The gang in ‘The Bikeriders’ are guys in jeans and leather who don’t look like they’ve come out of ‘Grease’

Christina Newland, film critic

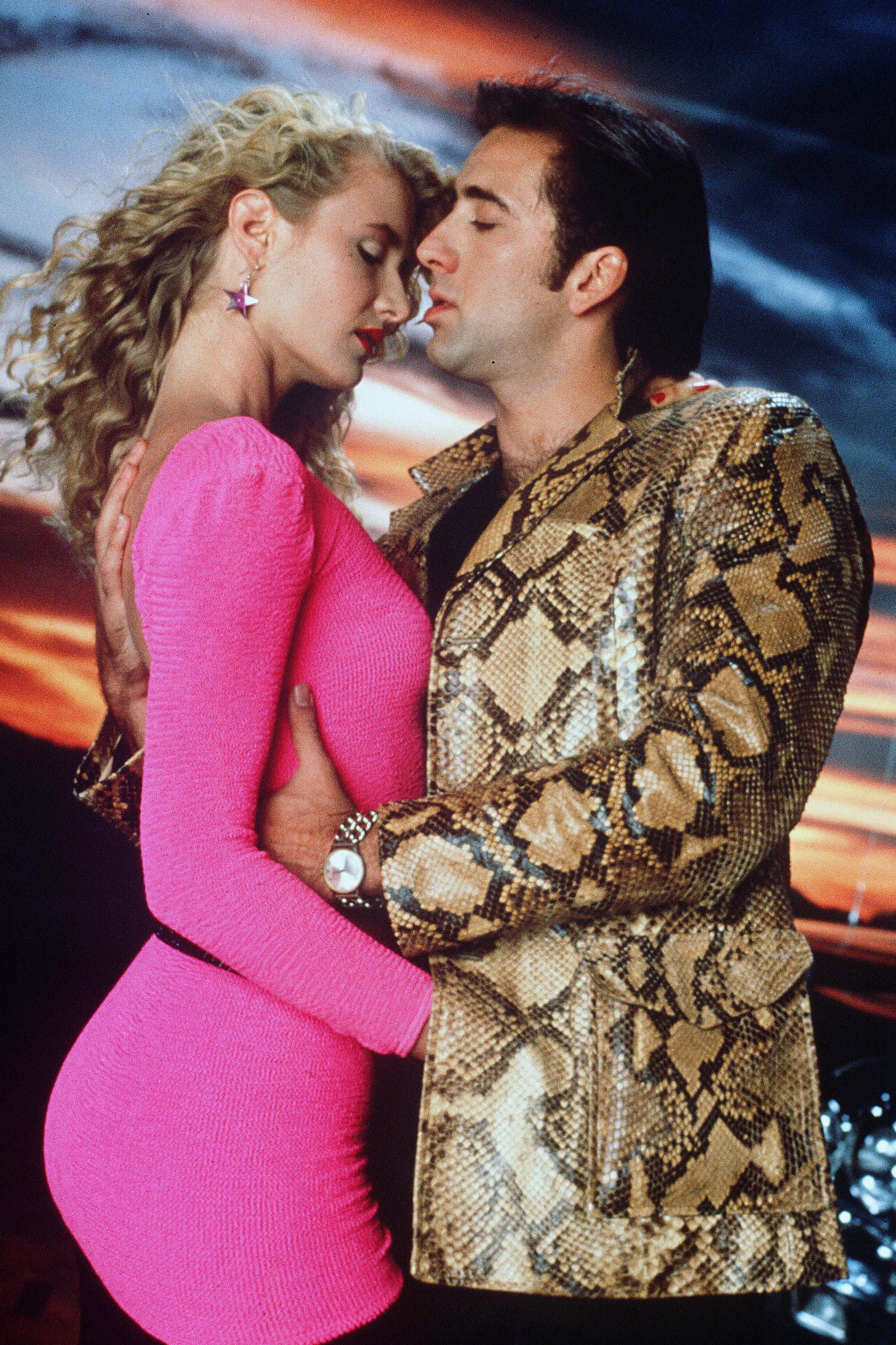

The leather jacket has, in its different forms, symbolised both rebellion and belonging. In the counterculture classic Easy Rider (1969), Peter Fonda’s Wyatt wears a tight-fit leather jacket with stars-and-stripes embroidered on the back, as he rides down American highways smoking weed and getting into trouble. Grease (1978) has two high school gangs: the T-Birds, with their black biker jackets, and the Pink Ladies, with their satin pink ones. In the teen TV series Riverdale, when narrator and local weirdo Jughead (Cole Sprouse) waltzes into school sporting a SouthSide serpents jacket, he immediately spreads fear and awe (or as much fear and awe as Sprouse can spread, I suppose). And in David Lynch’s surreal road movie Wild at Heart (1990), Nicolas Cage soliloquies about his snakeskin leather jacket ad nauseum: “Did I ever tell you that this here jacket represents a symbol of my individuality, and my belief in personal freedom?”

All of it can be traced back to Brando, whose performance as Johnny in The Wild One “spoke for the rising tide of youth culture, the birth of the teenager,” says Newland, “and he did it all with a leather jacket and a swagger in that famous exchange of dialogue: ‘Hey Johnny, whaddya rebelling against?’ ‘Whaddya got?’”

Brando’s performance directly inspired Elvis Presley’s costuming in Jailhouse Rock (1957) and, although James Dean doesn’t don a leather jacket in Rebel Without a Cause (1955), he was just as influenced by Brando’s work and rebellious attitude.

In the UK, leather jackets weren’t popularised until the early Sixties. Burton traces it back to rockabilly singer Gene Vincent’s first appearance on British television, on Jack Good’s Boy Meets Girls show in 1959, where he was outfitted in “full leather.” The Beatles played their infamous set in Hamburg wearing matching leather jackets, which became their onstage staple from 1960 through to 1962. And, of course, the warring subcultures of the time were the mods, in their suits and parkas, and the rockers, who wore their leather jackets and pompadours, directly inspired by The Wild One. Their scuffles led to widespread media coverage – youth culture was violent and unruly, the claim went, with outlets labelling them the UK’s “internal enemies”.

Years later, sociologist Stanley Cohen studied the phenomenon, coining the term “moral panic” in his 1972 book Folk Devils and Moral Panics to describe the outsized fury caused by fashion-conscious youths having fisticuffs on the beach. “When something becomes a street fashion, there’s always somebody who jumps on the bandwagon to make cheap, accessible items for kids,” recalls Burton, who himself provided the mod clothing for the classic coming-of-age film Quadrophenia (1978). “There were endless little adverts on the back of the music press for leather jackets.”

Over in France, fashion designer Yves Saint-Laurent, then head of Dior, tried to transform the leather jacket into a haute couture item. In 1960, inspired by American beatniks and counterculture, he presented a collection that featured leather. Critics and buyers, however, were not impressed. It wasn’t until the 1980s that the leather jacket became chic. With pop stars and celebrities like Madonna, Grace Jones and Cher donning leather jackets and custom-made leather outfits, it became “exclusive and expensive”. Since then, it’s become widely used in a variety of contexts, both on the runway and on screen.

Today, there’s nothing particularly underground about a leather jacket, but The Bikeriders grants it meaning once again. In the film, The Vandals are “guys in jeans and leather who don’t look like they’ve come out of Grease,” says Newland. The costumes, designed by Erin Benach, have a “lived-in quality. They are hard-wearing and heavily worn, practical items with snags and motor oil stains and scuffs.”

Nichols’s film reminds us that there was a time when the leather jacket was not something you could pick up in Zara, but a symbol of an attitude, a lifestyle and a commitment to a cause. It’s a reminder that the leather jacket, ever since Brando walked into that bar with his brash attitude, has always been a statement of intent.

‘The Bikeriders’ is in cinemas

[ad_2]

Source link